Tsukioka Yoshitoshi (月岡芳年)

|

The artist who is often called the last great master of ukiyo-e woodblock prints and paintings is Tsukioka Yoshitoshi (月岡芳年 1839–1892) whose original name was Owariya Yonejirô. Gifted, imaginative, and innovative, Yoshitoshi worked from the end of the Edo period until more than two decades into the Meiji period over the course of a 40-year career. He witnessed the collapse of the old feudal order and the embrace of Western culture and technology, which had a profound effect on Japanese society beginning with the signing of treaties opening up Japan to foreign trade in 1854. One senses this turmoil in much of Yoshitoshi's oeuvre as he sought to maintain previous cultural norms and artistic aims while also assimilating some of the new aspects of "enlightenment."

The artist who is often called the last great master of ukiyo-e woodblock prints and paintings is Tsukioka Yoshitoshi (月岡芳年 1839–1892) whose original name was Owariya Yonejirô. Gifted, imaginative, and innovative, Yoshitoshi worked from the end of the Edo period until more than two decades into the Meiji period over the course of a 40-year career. He witnessed the collapse of the old feudal order and the embrace of Western culture and technology, which had a profound effect on Japanese society beginning with the signing of treaties opening up Japan to foreign trade in 1854. One senses this turmoil in much of Yoshitoshi's oeuvre as he sought to maintain previous cultural norms and artistic aims while also assimilating some of the new aspects of "enlightenment."

Yoshitoshi was the son of a wealthy merchant named Owariya Kinzaburô (1815-1863) who was able to buy himself a position in the family of the samurai Yoshioka Hyôbu (1796-1855), which granted his children the use the Yoshioka surname. In 1850, when Yoshitoshi was 11 years old, he was apprenticed to Utagawa Kuniyoshi, who emphasized drawing from life. This mode of art was still unusual in Japanese painting academies and ateliers where capturing the essence of a subject was more highly prized than the "realism" found in Western art. Yoshitoshi also familiarized himself with Western drawing techniques, such as chiaroscuro and linear perspective, by studying Kuniyoshi’s collection of foreign prints and engravings. It appears that Yoshitoshi also studied for a time with the painter Kikuchi Yôsai (菊池容斎 1781-1878), who had trained in Kanô, Shijô, and Maruyama styles, passing on some of that knowledge to the younger artist who then developed his own eclectic manner.

Yoshitoshi's first published woodcut was a triptych in 6/1853 titled Bunji gannen Heike ichimon horobi kaichû ni ochiiru zu (In the first year of the Bunji era [1185], the Heike clan fell into the sea and perished: 文治元年平家の一門亡海中落入る圖) portraying the defeat of the Heike (Taira) by the Genji (Minamoto) at the battle of Dannoura (see image below). Issued when he was only 14 years of age (15 by Japanese reckoning), the design displays remarkable maturity and sure-handedness for a young teenager, even if derivative of his teacher Kuniyoshi's late triptychs. There is then a gap of about five years before the next known datable work, a triptych titled Edo no hana kodomo asobi no zu (Flowers of Edo: a view of children's games: 江戸の花子供遊の圖) issued in 1858.

|

| Yoshitoshi: Bunji gannen Heike ichimon horobi kaichû ni ochiiru zu, 6/1853 |

Yoshitoshi produced few prints during the first eight years of his career, but in 1862 at least 44 designs were published, and during the next two years another 63 designs, mostly kabuki prints. It so happened that many of his prints in the 1860s were depictions of graphic violence and death (so-called chimamiri-e or "blood-stained pictures": 血塗絵). Some scholars link the death of Yoshitoshi's father Owariya Kinzaburô (1815-1863) with this subject matter; others suggest that growing lawlessness and violence during the final years of the Tokugawa feudal system also played a role.

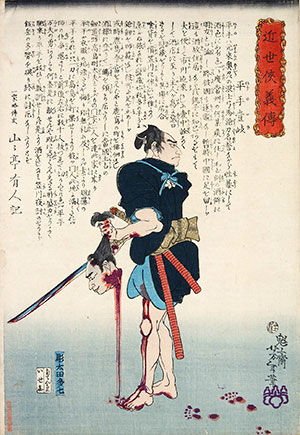

In 1865, ninety-five more designs appeared, mostly on military and historical subjects. Between 1865 and 1868, Yoshitoshi produced some very disturbing images, notably in two series: Kinsei kyôgiden (Biographies of modern men: 近世侠義伝), comprising 36 prints published by Iseki (Manyôdô) and carved by hori ôta Tashichi from 10/1865 to 4/1866; and Eimei nijûhasshûku (Twenty-eight famous murders with verses: 英名二十八衆句), published from 12/1866 to 5/1867 by Sanoya Tomigorô (Kinseidô), carved by hori ôta Tashichi and Matsushima hori Masa. Yoshitoshi collaborated on this second series with another Kuniyoshi pupil Utagawa Yoshiiku (歌川芳幾, 1833-1904), with each contributing 14 designs. The two artists portrayed gruesome acts of murder or torture based on historical events or scenes from kabuki plays. At the lower left is a depiction by Yoshitoshi of Hirade Ike holding the severed head of an enemy, as blood pours down from the open neck and Hirade's leg. In another example at the lower right, Danshichi Kurobei (団七九郎兵衛) is shown slashing his evil father-in-law Mikawaya Giheiji (三川屋義平二) in the "Nagamachi Ura" (backstreet) murder scene made famous in the play Natsu matsuri Naniwa kagami (Mirror of the Osaka Summer Festival: 夏祭浪花鑑). Yoshitoshi's approach is about as gruesome as one might find in ukiyo-e, emphasizing the brutal physical act with Giheiji covered in mud and screaming in terror. Compare the very different, far-more "interior" psychological treatment of the same scene by the Osaka artist Shunbaisai Hokuei more than three decades earlier. Unfortunately, these and other "bloody prints" (muzan-e, cruelty, 無残絵) have often been over-sold by some critics, leading to a distorted perception of Yoshitoshi as a decadent sensationalist, which fails to account for the diversity of subjects in his oeuvre.

|

|

| Yoshitoshi: Hirade Ike (平手壱岐) with severed head Series Kinsei kyôgiden, 1865 |

Yoshitoshi: Danshichi Kurobei (団七九郎兵衛) kills Giheiji Series: Eimei nijûhasshûku (12/1866) |

At the start of the 1870s, print sales slowed and Yoshitoshi began to exhibit signs of severe depression, which may have led to a complete mental breakdown in 1872. However, by 1873 he seemed to recover, changing his art pseudonym from "Ikkaisai" (一魁齋) to "Taiso" ("great resurrection": 大蘇). Around this time he produced nishiki-e shinbun (color-picture newspapers: 錦絵新聞) for the so-called nichinichi shinbun (daily newspapers: 日々新聞 actually issued from every few days to once every month or two). These images were woodblock printed illustrations (typically full-page) that accompanied articles featuring the bizarre and bloody, crimes of passion and tales of envy, love suicides and vendettas, and stories of bravery and tales of ghostly apparitions.

During the 1880s, Yoshitoshi produced many of his finest works, both as single designs and in series. This was also a decade during which the woodblock print as an art form was slowly dying as Japan modernized and began to adopt Western forms of image-making, including lithography. Nevertheless, Yoshitoshi continued to insist on the highest standards of woodblock carving and printing, which some critics have asserted helped save, temporarily, the genre of ukiyo-e printmaking from oblivion.

|

|

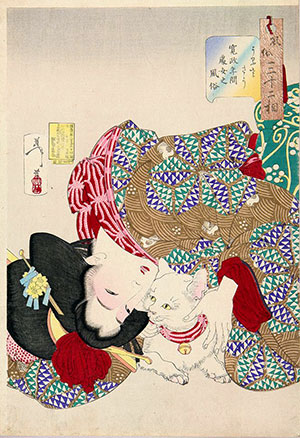

| Yoshitoshi: Tiresome (girl playing with cat) Series: Fûzoku sanjûnisô, 1888 |

Yoshitoshi: Strolling (upper-class wife) Series: Fûzoku sanjûnisô, 1888 |

An important series by Yoshitoshi from the late 1880s was Fûzoku sanjûnisô (Thirty-two aspects of daily life: 風俗三十二相) of 1888, a remarkable set that featured portrayals of beauties from different social classes. (An alternate translation could be "Thirty-two aspects of customs and manners.") The first image shown above left is titled Urusasô Kansei nenkan shojo no fûzoku (Tiresome — the appearance of a virgin of the Kansei era: うるささう寛政年間処女之風俗) from February 1888. A young girl from a wealthy family, is with elegant coiffure and a fine uroko (fish-scale: 鱗) patterned robe, plays with her cat. We are reminded here, of course, that Yoshitoshi's teacher, Kuniyoshi, was entirely devoted to cats, as the felines appear frequently in his prints. A second example, above right, is titled Sanpogashitasô Meiji nenkan saikun no fûzoku (Strolling — the appearance of an upper-class wife of the Meiji era: 遊歩がしたそう明治年間妻君之風俗) from June 1888. Yoshitoshi portrayed an affluent young beauty adorned in the latest Western fashion. She is walking among irises, possibly in the Horikiri Shobuen (Iris Garden at Horikiri: 堀切菖蒲園) in Tokyo. The colorful, eye-catching depiction of Western dress would have aroused some discomfort at a time when conflicts were widespread over the assimilation of customs and manners from the West. Although one could argue that Yoshitoshi's "upper-class wife" was but another variant on traditional ukiyo-e prints featuring women adorned in the latest fashions, this one brings with it some controversy. It grates against the nostalgic view of Japanese women otherwise presented in the series. Moreover, the modern-day beauty's attire — so brilliantly observed by Yoshitoshi — might not have met with his approval, given his sadness over the passing of the old ways in Japan. Despite all this, the design was reprinted many times to meet popular demand and most surviving impressions show some block wear.

Yoshitoshi's masterpieces of the 1880s included several triptychs, foremost among them his Fujiwara no Yasumasa gekka rôteki zu (Fujiwara no Yasumasa playing flute by moonlight: 藤原保昌月下弄笛図) from 1883. The left sheet has a long inscription reading Meiji jûgo mizunoe-uma kishû Kaiga Kyôshinkai shuppinga Fujiwara no Yasumasa gekka rôteki zu, ôju ("Fujiwara no Yasumasa playing the flute by moonlight," a painting shown at the picture exposition of the National Painting Exhibition in autumn 1882, by request: 明治十五壬午季秋絵画共進会出品画藤原保昌月下弄笛図 応需). The original vertical-format painting, ink and color on silk measuring 1,423 x 785 mm, was submitted in 1882 to the Naikoku Kaiga Kyôshinkai (National Competitive Painting Exhibition) as part of its first public showcasing of traditional Japanese art. The exhibition was sponsored by the Ministry of Agriculture and Trade, which excluded Western-style paintings in an effort to revitalize and promote Japanese art.

|

| Yoshitoshi: Fujiwara no Yasumasa gekka rôteki zu, 1883 |

Close behind, if not the equal of the Yasumasa triptych, was the triad of impressive triptychs from 1890 on the theme of Setsugekka no uchi (Set of snow, moon, flowers: 雪月花之内), published by Akiyama Buemon. The design shown below is for the tsuki or getsu (moon: 月) subject. This bold work portrays the superstar actor Ichikawa Sanshô (市川三升 poetry name of Danjûrô IX) as the pirate Kezori Kuemon (毛剃九右衛門) at the moment when Kezori challenges a Kyoto merchant named Komachiya Sôshichi to a duel over their rivalry for the courtesan Kojorô. It is said that Yoshitoshi spent three days drawing Kezori's hair, beard, and wig, and asked a friend, the haiku poet Katsurakaen Keika (1829-99), to provide the calligraphy for the actor and role names in the square cartouche. Katsurakaen also supplied the calligraphy for the 100 Moons series (see first image at the top right of this page and related text below).

_300w.jpg) |

| Yoshitoshi: (Moon) Ichikawa Sanshô as Kezori Kuemon, 1890 |

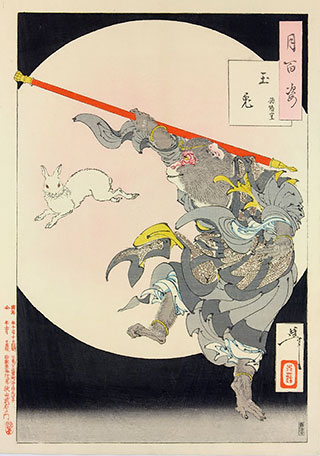

By the time of Yoshitoshi's death in 1892, he had produced a number of important themed sets. His creative imagination was given full reign in his later series, among these Tsuki hyakushi (100 aspects of the moon: 月百姿), published from 10/1885 to 12/1891, in which a startling range of subjects and moods prevailed. The example at the top of this page is titled Gyukuto — Songokû (Jade rabbit — Sun Wukong: 玉兎 孫悟空) and depicts the immortal monkey Songokû (孫悟空) playing with the Rabbit in the Moon or Jade Rabbit (玉兎), dated 11/1889. A white rabbit was associated with the moon in early Japanese folklore, and various myths attend to both of these mythological animals. With this design, Yoshitoshi struck an playful chord, an approach toward print design for which he is rarely given credit.

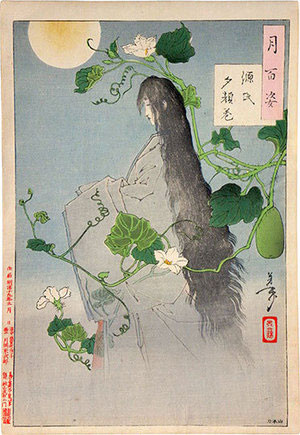

Another print from the moon series is titled Genji yûgao no maki (Yûgao chapter from Genji: 源氏夕顔巻) from 3/1886. Yoshitoshi portrayed the ghost of one of Prince Genji's lovers whom he called Yûgao ( 夕顔 named after white "evening flowers": also called "moon flowers") that bloomed in her overgrown garden. After they consummated their love, Yûgao quickly died, murdered by a jealous spirit of one of Genji's former mistresses. The printing here is nuanced, with the lower part of the ghost fading into nothingness at the bottom of the design.

|

|

| Yoshitoshi: Ghost of Yûgao Series:Tsuki hyakushi, 3/1886 |

Yoshitoshi: Ghost of Okiku Series: Shingata sanjûrokkaisen, 8/1890 |

Another fine late series was Shingata sanjûrokkaisen (New forms of thirty-six ghosts: 新形 三十六怪撰) of 1889–1892. One famous design is similar to the Yûgao subject in its rendering of a transparent ghostly form, which is best demonstrated in an early delicate printing such as the one above right (see comparison at Editions). The design is titled Sarayashiki Okiku no rei (Ghost of Okiku at Sarayashiki: 皿やしき於菊の霊). The legend recounts a false accusation against Okiku, a maid in the household of a low-ranking samurai named Aoyama Tessan. When his wife breaks a valuable imported porcelain dish, one of ten such heirlooms, she blames it on the maid. Punished and shamed, Okiku drowns herself in the family's well. Every night they are subjected to her wailing and counting aloud to "nine." Finally, the spirit of Okiku is appeased when a family friend waits for Okiku to finish her count, whereupon he firmly calls out "ten."

In his final year or two, Yoshitoshi's mental problems recurred as he suffered from delusions while his physical condition also deteriorated. He died on June 9, 1892 from a cerebral hemorrhage at the age of fifty-three. A stone memorial monument to Yoshitoshi was erected by many of his pupils in Mukojima Hyakkaen garden, Tokyo, in 1898.

Yoshitoshi was arguably the finest ukiyo-e print designer of the late nineteenth century. His figures were vividly realized and invested with a realism that relied, not insignificantly, on superb drawing ability. As he broke away from stagnating convention, Yoshitoshi's seemingly unfettered imagination found expression in many subjects: history, folklore, legend, warrior tales, women, daily life, and old and new customs. He was uniquely gifted as a visual artist and a connoisseur of stories about Japanese and Chinese history and legend. By bridging the transition from the feudal society of the Edo period to the enlightenment restoration of the Meiji period, he succeeded in revitalizing ukiyo-e in unexpected ways. ©1999-2019 by John Fiorillo

See also the discussion of Yoshitoshi prints used to illustrate the Editions.

Tsukioka Yoshitoshi's Names

Surnames:

Surnames:

Owariya (surname of his father Kinzaburô 金三郎 1815-1863 not used in signatures)

Yoshioka (吉岡 after his father purchased a position in the Yoshioka samurai family

Tsukioka (月岡 used occasionally c. 1865 until c. 1875)

Taiso (大蘇 "Great Resurrection"; used exclusively after 1873)

Personal Name (jinmei):

Yonejirô (米次郎)

Art Names (geimei):

Yoshitoshi

(芳年)

Art Pseudonyms (gô):

Ikkaisai (ー魁さ齋 first appeared in c. 1853)

Kaisai (魁齋)

Gyokuôrô (玉桜楼 or Gyokuô 玉桜 used between c. 1859 and c. 1861)

Sokatei (咀華亭)

Pupils of Tsukioka Yoshitoshi

Yoshitoshi had an enormous number of pupils. For some, usually younger pupils, he provided boarding; for others, usually older pupils, he welcomed their visiting periodically. Still others were daily visitors to his studio. One of his pupils, Yamanaka Kodô (山中古洞 1869-1945), wrote a episodic, meandering biography of his master (Yoshitoshi nishiki-e nenpyô, "Chronology of Yoshitoshi's color woodblock prints," serialized in Ukiyo-e shi, "Ukiyo-e Magazine," nos. 11-12, 1929) in which he claimed that Yoshitoshi had more than 200 students in the mid-1880s, and that he bestowed gô upon at least 60 of them [Keyes, Courage and Silence (dissertation), 1983, p. 535]. It appears that all artists of the late nineteenth century whose names begin with the character for "Toshi" (年) were his pupils.

The following list of about 40 students is not meant to be definitive, but simply to provide some idea of the extent of Yoshitoshi's involvement in tutoring artists. Some of the identifications are tentative, as are a few of the Japanese characters, as various sources differ. The order given below is by geimei (art names, i.e., not the gô "prefixes").

Kobayashi Eitaku (小林永濯 1843-1890; other gô Sensai 鮮齋, Issensai 一鮮齋, Baikodô 梅花堂, Kadô 霞堂, Mugyo 夢魚)

Kasai Hôsai (笠井鳳齋 student in 1880s)

Takeuchi Keishû (武内桂舟 1861-1943)

Yamanaka Kodô (山中古洞 1869-1945; also Tatsushige 辰重) and Tatsujû; pupil in the 1880s)

Tsukioka Kôgyo (月岡耕漁 1869-1927; also Tsukioka Toshihisa 月岡年之)

Saitô Nengyo (齋藤年魚 student in 1880s)

Nishii Nenka (西井年寛 student in 1880s)

Ozaki Nenka (尾崎年華 also Chôsai 晁斎, Sanyô 三容)

Nishii Nenkan (西井年寛 pupil in 1880s, also studied with Mori Kansai, later geimei Kinsai)

Hanawa Nenkô (花輪年香 named as deceased on Yoshitoshi memorial of 1892)

Katsura Nenkyo (桂年擧 died c. 1897; earlier geimei Tsunehide and later Gyokuto)

Tominaga Toshichika (富永年親 1847-c. 1887)

Nozaka Toshiharu (野阪年晴 1843-? an early pupil)

Migata Toshihide (右田年英 1862(3)-1925 pupil from 1884, gô Gosai 梧斎, Ichieisai 一潁斎, Bansuirô 晩翠楼)

Toshihiro (年廣 an early pupil)

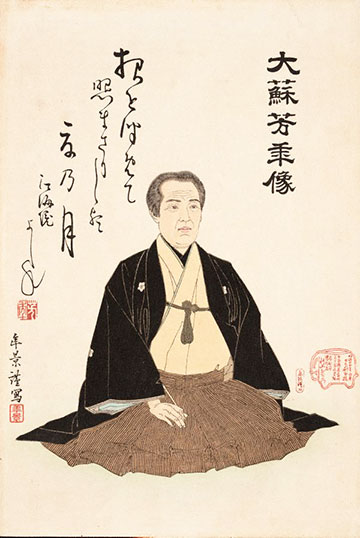

Kanaki Toshikage (金木年景 act. c. 1868-1892; known for 6/1892 memorial portrait of Yoshitoshi, above right)

Mizuno Toshikata (水野年方 1866-1908; other gô ôsai 応斉 Shôsetsu 蕉雪)

Hosoki Toshikazu (細木年一 act. c. 1877-1879; other gô Seisai)

Fuse Toshimaro (布施年麿 Yoshitoshi's first pupil in 1860)

Fukushima Toshimaru (福島年丸 personal name Seijirô 清次郎; pupil in the 1880s)

Utagawa Toshimasa (歌川年昌 act. c. 1890s, gô Shunsai 春齋 pupil until 5/1890, then studied with Utagawa Kunitama [Hôsai])

Tsutsui Toshimine (筒井年峰 1863- until or after 1934?)

Kobayashi Toshimitsu (小林年光 act. c. 1876-1904; geimei Toshichika 年家 gô Teisai 亭齋, Kôsai 高齋, Shinsai 進斉 early pupil)

Suzuki Toshimoto (鈴木年基 [also 鈴樹年基] act. c. 1877-c. 1890s)

Utagawa Yoshimune II (歌川芳宗 1863-1941; early art name Arai Toshiyuki 新井年雪, gô Isshôsai; became student c. 1876)

Inagaki Toshinao (稲垣年直 pupil in 1870s)

Shibata Toshindo (柴田年人 personal name Nobuko のぶ子 younger sister of artist Tanba Reizan, wife of painter Shibata Hôshû)

Kifuji Toshinobu (木藤年延 probably an early student)

Shirai Toshinobu II (白井年信 1866-1903; other geimei Kuniume 国梅 gô Shûsai 修斉)

Yamazaki Toshinobu I (山崎年信 1857-1886; other gô Sensai 仙斎, Nansai 南斎, Goen 呉園, Fusoen 扶桑園 pupil in 1870s)

Yamada Toshisada (山田年貞)

Yamada Toshitada (山田年忠 1868-1934; geimei Toshinaka 年中, Keichû 敬中, gô Shimane 島根, Nansai 南齋, Nanshi 南志, Katoku 可得)

Fuse Toshitaka (布施年鷹)

Ozaki Toshitane (尾崎年種 act. c. 1882-1897; other gô Gyokkyaku 玉客)

Toshitoyo (年豊 early pupil)

Nakayama Toshitsugu (中山年次 1840-1900 an early pupil)

Inano Toshitsune (稲野年恒 1859-1907 pupil in 1870s, later studied with painter Kôno Barei)

Fujishima Toshiyoshi (藤島年美 student in c. 1870s, again in 1880s; later geimei Eiryû 永柳 and Kasen 華僊)

Arai Toshiyuki (新井年雪 pupil at age 12 in 11/1881; gô Isshôsai 一松斉, later name Yoshimune II 芳宗)

BIBLIOGRAPHY

- Keyes, Roger: The Bizarre Imagery of Yoshitoshi: The Herbert R. Cole Collection. Los Angeles County Museum of Art, 1980.

- Keyes, Roger: Courage and Silence. A Study of the Life and Color Woodblock Prints of Tsukioka Yoshitoshi, 1839-1892 (vols. 1-2). Ann Arbor: University Microfilms, Dissertation, Union for Experimenting Colleges and Universities, 1983.

- Newland, Amy Reigle: The Hotei Encyclopeida of Japanese Woodblock Prints. Amsterdam: Hotei Publishing, 2005, Vol. 2, pp. 499 and 530.

- Roberts, Laurance: A Dictionary of Japanese Artists: Painting, Sculpture, Ceramics, Prints, Lacquer. Tokyo/New York: Weatherhill, 1976, p.204.

- Segi, Shinichi: Yoshitoshi: The Splendid Decadent. (Trans. by Alfred Birnbaum) Tokyo/New York: Kodansha, 1985.

- Stevenson, John: Yoshitoshi's One Hundred Aspects of the Moon. Redmond, San Francisco Graphic Society, 1992.

- Stevenson, John: Yoshitoshi's Women: The Print Series Fuzoku Sanjuniso. Avery Press, 1986 (first ed.) and 1995 (rev. ed.).

- Stevenson, John: Yoshitoshi's Thirty-Six Ghosts. New York: Weatherhill, 1983.

- Stevenson, John: Yoshitoshi’s Strange Tales. Amsterdam: Hotei Publishing, 2005.

- van den Ing, Eric and Schaap, Robert: Beauty & Violence: Japanese Prints by Yoshitoshi 1839-1892. Eindhoven: Haviland Press, and Amsterdam: Society for Japanese Arts, 1992.

Viewing Japanese Prints |