FUJIMORI Shizuo (藤森静雄)

|

Fujimori Shizuo (藤森静雄), born in Kurume, Fukuoka Prefecture, lost his right thumb in a childhood accident, but nevertheless was able to carve woodblocks starting in the 1910s. He enrolled in the Hakubakai Institute of Western Painting in 1910, where he became friends with Tanaka Kyôkichi. He was accepted into the Tokyo School of Fine Arts in 1911 (graduated 1916), where early on he met Onchi Kôshirô. Together, the three young artists produced the seminal poetry and print magazine Tsukuhae ("Moonglow": 月映), issued from September 1914 until November 1915, when Tanaka's premature early death ended the project after seven issues. Apparently, during this period, the expressionism that was central to Onchi and Tanaka influenced Fujimori, whose designs (a total of 37 for Tsukuhae) incorporated the early style that the two more adventurous artists were pursuing.

Fujimori Shizuo (藤森静雄), born in Kurume, Fukuoka Prefecture, lost his right thumb in a childhood accident, but nevertheless was able to carve woodblocks starting in the 1910s. He enrolled in the Hakubakai Institute of Western Painting in 1910, where he became friends with Tanaka Kyôkichi. He was accepted into the Tokyo School of Fine Arts in 1911 (graduated 1916), where early on he met Onchi Kôshirô. Together, the three young artists produced the seminal poetry and print magazine Tsukuhae ("Moonglow": 月映), issued from September 1914 until November 1915, when Tanaka's premature early death ended the project after seven issues. Apparently, during this period, the expressionism that was central to Onchi and Tanaka influenced Fujimori, whose designs (a total of 37 for Tsukuhae) incorporated the early style that the two more adventurous artists were pursuing.

Fujimori studied with the yôga (Western-style: 洋画) painters Kuroda Seiki (黒田清輝 1866-1924) and Fujishima Takei (藤島武二 1867-1943), and was inspired by another yôga painter, Shigeru Aoki (青木繁 1882-1911). For a few years, Fujimori taught in middle schools on Taiwan (where he gave lessons in block carving to Yamaguchi Gen) and in Fukuoka, but then moved to Tokyo in 1922 to work as a full-time artist. In 1939 he returned to live in Iizuka, Fukuoka Prefecture, where he remained until his death in 1943.

Fujimori was a founding member of Nihon Sôsaku Hanga Kyôkai (Japan Creative Print Association: 日本創作版画協会) in 1918 and contributed to their first exhibition in 1919. Working once again with Onchi (and Ôtsuki Kenji) in 1921, he started the general art magazine Naizai. Dedicated to promoting hanga, Fujimori contributed to various print magazines. In 1931 he became a founding member of the Nihon Hanga Kyôkai (Japan Print Association: 日本版画協会). Around 1936 he began to produce woodblock illustrations for serials in the Fukuoka Asahi Shinbun newspaper, including some for a serialized novel by Chikamatsu Shûkô (近松秋江 1876-1944). Throughout his career, Fujimori contributed to dôjin zasshi (coterie magazines: 同人雑誌), including Shi to hanga ("Poetry and prints," 1922-25), Kaze ("Wind," 1927-28), Bijutsu-han ("Art prints," 1932-34), Han geijutsu ("Print art," 1932-36), and Kasuri ("Ikat fabric," 1934-36).

Fujimori contributed 13 designs to the grand series of prints titled Shin Tokyo hyakkei (One hundred views of new Tokyo: 新東京百景) published from 1929 to 1932, joining Onchi Kôshirô, Hiratsuka Un'ichi, and six other artists. He also produced his own series of meisho (famous views: 名所), titled Dai Tokyo jûnikei no uchi (Series of twelve views of great Tokyo: 大東京十二景の内), 1932-34, for which he designed a scene for each month.

Fujimori contributed 13 designs to the grand series of prints titled Shin Tokyo hyakkei (One hundred views of new Tokyo: 新東京百景) published from 1929 to 1932, joining Onchi Kôshirô, Hiratsuka Un'ichi, and six other artists. He also produced his own series of meisho (famous views: 名所), titled Dai Tokyo jûnikei no uchi (Series of twelve views of great Tokyo: 大東京十二景の内), 1932-34, for which he designed a scene for each month.

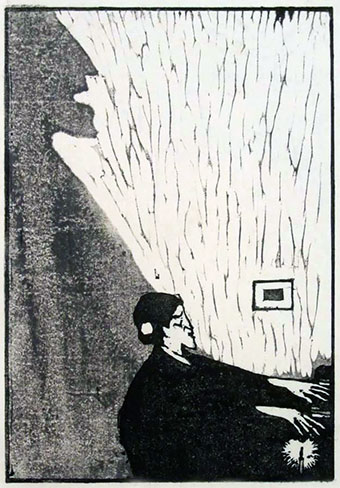

The woodcut at the top right is known as Yûgata no piano (Piano in the evening: 夕方のピアノ), or alternatively, Yoru no uta (Night song: 夜のうた), which was included in the volume II of Tsukuhae in 1914. Fujimori produced a number of designs with figures casting shadows, with some suggesting isolation, mystery, or foreboding. The shadow in Yûgata no piano is the most dramatic of all. Its full meaning is difficult to discern, and perhaps that's the point — a symbolist design intended to conjure up emotions different for each observer.

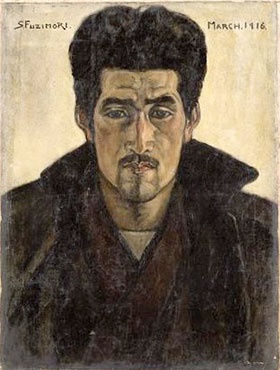

The painting on the left is a self-portrait from March 1916, the year Fujimori graduated from the Tokyo School of Fine Arts. Done as a yôga (Western-style) painting, it demonstrates sufficient mastery of the pictorial mode taught in the school. The figurative realism is very different from what he was exploring, along with Onchi and Tanaka, in their radical expressionistic designs for Tsukuhae.

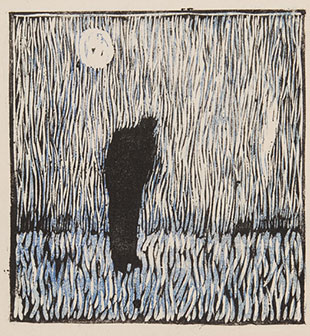

A recurring motif in Fujimori's early work is the isolated figure. These portrayals are often suffused with a mood of anxiety or sinister vulnerability. Around the time that the volume II of Tsukuhae was published in 1914, Fujimori designed a small (167x147mm) untitled woodcut depicting a solitary slumped-over figure standing in a field. The shapes of the leaves of grass are echoed by a sky filled with radiating, unnatural, curving lines. A pale blue tint has been applied throughout the pictorial space, stronger nearer the lower third. The scene emits a feeling of oppression, suggesting the figure bears a tragic burden. It would not be too speculative to suggest that, at least in part, the illness (tuberculosis, contracted in 1913) of Fujimori's friend and artistic partner Tanaka Kyôkichi played a role in this visualization.

A recurring motif in Fujimori's early work is the isolated figure. These portrayals are often suffused with a mood of anxiety or sinister vulnerability. Around the time that the volume II of Tsukuhae was published in 1914, Fujimori designed a small (167x147mm) untitled woodcut depicting a solitary slumped-over figure standing in a field. The shapes of the leaves of grass are echoed by a sky filled with radiating, unnatural, curving lines. A pale blue tint has been applied throughout the pictorial space, stronger nearer the lower third. The scene emits a feeling of oppression, suggesting the figure bears a tragic burden. It would not be too speculative to suggest that, at least in part, the illness (tuberculosis, contracted in 1913) of Fujimori's friend and artistic partner Tanaka Kyôkichi played a role in this visualization.

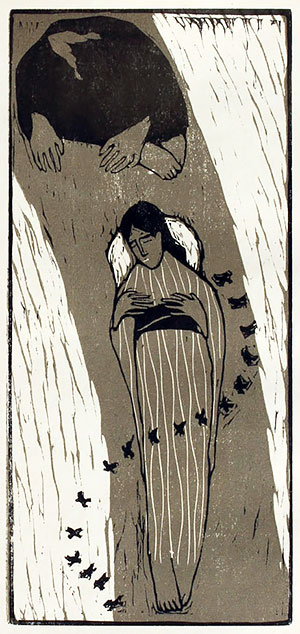

Narrative works with elongated figures also appear in Fujimori's early oeuvre. Illness serves as the explicit theme for a small woodcut (image 196 x 91 mm) known as Imôto wa yaminu ("My sister is sick": 妹は病みぬ) from October 1914. The design appeared in volume II of Tsukuhae. The sister is laid out as if she were a corpse, her hands placed on her chest and feet overlapping. Her brother sits bent over in anguish above her. Flowing lines are carved on either side of a central band of brown, while a flock of black birds fly above her prone body in a symbolic reversed "S" formation. Her body is not securely fixed in space, as if she could float down the brown band or stream, into oblivion.

In a very different mode, Fujimori produced more conventional designs for several series of meisho (famous views: 名所). As mentioned earlier, he contributed 13 designs to the grand series of prints titled Shin Tokyo hyakkei (One hundred views of new Tokyo: 新東京百景) in 1929-1932. The aim of the series was both commercial and cultural. The publisher and artists hoped to sell their works and establish a larger audience for modern prints. Moreover, they wanted to celebrate the city of Tokyo rising from the ashes of the 1923 earthquake. All the artists in this series designed fairly conventional views, for easy identification of the meisho, to encouragee sales, and to promote sôsaku hanga (creative prints: 創作版画). Rendered in the modern sôsaku hanga style, many of the forms in the designs were carved and printed with soft edges, thus no longer relying on the traditional black outlines characterizing ukiyo-e (Edo-period prints of the floating world: 浮世絵) or shin hanga ("new prints" or neo-ukiyo-e: 新版画).

In a very different mode, Fujimori produced more conventional designs for several series of meisho (famous views: 名所). As mentioned earlier, he contributed 13 designs to the grand series of prints titled Shin Tokyo hyakkei (One hundred views of new Tokyo: 新東京百景) in 1929-1932. The aim of the series was both commercial and cultural. The publisher and artists hoped to sell their works and establish a larger audience for modern prints. Moreover, they wanted to celebrate the city of Tokyo rising from the ashes of the 1923 earthquake. All the artists in this series designed fairly conventional views, for easy identification of the meisho, to encouragee sales, and to promote sôsaku hanga (creative prints: 創作版画). Rendered in the modern sôsaku hanga style, many of the forms in the designs were carved and printed with soft edges, thus no longer relying on the traditional black outlines characterizing ukiyo-e (Edo-period prints of the floating world: 浮世絵) or shin hanga ("new prints" or neo-ukiyo-e: 新版画).

The Kabuki-za has had a rather unsettled history. It was originally opened in 1889 by a Meiji-era journalist named Fukuchi Gen'ichirô, who wrote kabuki dramas in which the superstar Ichikawa Danjûrô IX (1838-1903) and other actors performed. Fukuchi retired from management when Danjûrô died in 1903, and eventually the Shochiku Corporation took over in 1914. An electrical fire destroyed the building on October 30, 1921, and while reconstruction was ongoing, the Great Kantô Earthquake of September 1, 1923 brought it down again. Rebuilding was finally completed in 1924.

Unfortunately, the theater was destroyed once more, this time by Allied bombing during World War II. It was restored in 1950, preserving the style of the 1924 reconstruction. A final demise and rebirth of the theater took place when the 1950 structure was demolished in the spring of 2010, and then rebuilt over the ensuing three years, once again using the baroque Japanese revivalist style of the 1924 building, intended to evoke the architectural details of Japanese Edo-period castles.

Fujimori's depiction of the Kabuki-za from 6/1930 (see immedaitely below) shows the front of the 1924 building. An electric street car passes by as theater fans step out of their vehicles to climb the stairs leading up to the main entrance. The scene is aglow in yellow incandescent light of what was then modern Tokyo. Yellow and black dominate the view. Using an economy of means, Fujimori captured the brilliance and grandeur of the Kabuki-za.

|

| Fujimori: Yoru no kabuki-za (Kabuki theater at night: 夜の歌舞伎座), 6/1930 Collaborative series: Shin Tokyo hyakkei (One hundred views of new Tokyo: 新東京百景) |

Fujimori's Dai Tokyo jûnikei no uchi (Series of twelve views of great Tokyo: 大東京十二景の内) starts off with "January, morning view of Meiji-jingû at Shibuya-ku": 一月 朝の明治神宮 (渋谷区) from 2/1933, shown immediately below. (The designs for the 11th and 12th views were actually completed earlier, in 1932.) The Meiji Shrine (Meiji Jingû: 明治神宮) is a Shinto shrine dedicated to the deified spirits of Emperor Meiji (1852-1912) and his wife, Empress Shôken (1849-1914). Construction began in 1915, formal dedication was held in 1920, and the shrine completed in 1921. The grounds were officially finished by 1926. Fujimori's design preserves the appearance of the first torii (shrine gate: 鳥居) and the shrine beyond it, as the site was destroyed during the Tokyo air raids in World War II. The shrine was rebuilt and finished in October 1958.

|

| Fujimori: January, Morning view of Meiji-jingû Shrine (Shibuya-ku): 一月 朝の明治神宮 (渋谷区), 2/1933 |

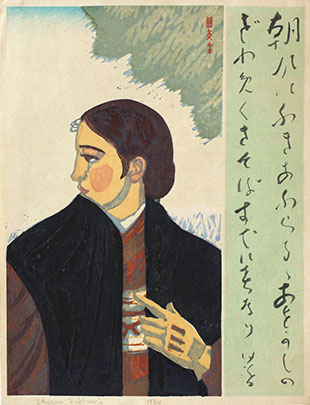

Continuing with a more conventional mode of imagery than he produced in the 1910s, Fujimori also designed a few bijinga (pictures of beautiful women: 美人画) and seibutsu-ga (still life: 静物画), although not in the competing shin-hanga or neo-ukiyo-e manner. In the design below left, a young woman is dressed in warm winter clothing. The poem inscribed along the right side is by Yosano Akiko (與謝野晶子 1878-1942), a pioneering feminist poet, pacifist, and social reformer. She was one of the most noted, and most controversial, post-classical female poets in Japan. As for the print, Fujimori probably owed a debt to Onchi, whose portraits of women in the 1920s and early 1930s helped to establish this particular sort of sôsaku-hanga style of portraying young women. One thinks, for example, of Onchi's Bijin shiki (Beauties of the four seasons: 美人四季) from 1927, or his Imayo fujin hattai no uchi (Eight beauties of modern times: 今代婦人八態のうち), for which only four designs are known, from the years 1929-1935.

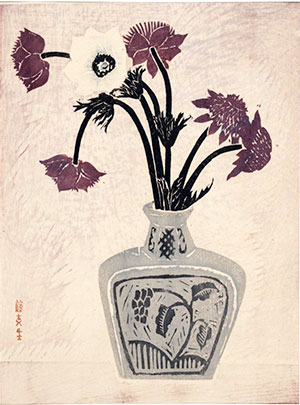

In 1934, Fujimori completed a still life of anemones in a vase decorated in a mingei (folk art: 民芸) style. An impression of the print was among 246 modern works shown by the Nihon Hanga Kyôkai (Japan Print Association: 日本版画協会) at an exhibition given at the Musée des Arts Décoratifs in Paris in 1934. The show was dedicated to sôsaku hanga, the self-carved, self-printed works promoted by Onchi and others. However, there were also more than 400 other prints, mostly ukiyo-e and a few self-published, artisan-printed shin hanga.

|

|

| Fujimori: Woman in winter clothing, 1930 (330 x 251 mm) | Fujimori: Anemones in July, 1934 (319 x 245 mm) |

From his early years as an expressionist-symbolist print designer, and a friend-colleague of Onchi Kôshirô and Tanaka Kyôkichi, until his middle and later years when he adopted more conventional motifs and styles, Fujimori Shizuo was one of the most active artists in the sôsaku hanga movement. His engagement with various print organizations and coterie magazines helped to promote sôsaka hanga before the Second World War. Even so, it will probably remain true that his contributions to the seven volumes of the 1914-1915 Tsukuhae magazine will be considered his most important achievement. © 2020 by John Fiorillo

BIBLIOGRAPHY

- Ajioka, Chiaki, Nishiyama, Chuko, Kuwahara, Noriko: Hanga: Japanese Creative Prints. Sydney: Art Gallery of New South Wales, 2000, pp. 50, 52 and 99.

- Ajioka, Chiaki, "The nature of artistic groupings: sôsaku hanga and the Japan Creative Print Association," in: Uhlenbeck, C., Newland, A.R., de Vries, M.: Waves of renewal: modern Japanese prints, 1900 to 1960. Leiden: Hotei Publishing, 2016, pp. 65-68.

- Fujii, Hisae: Onchi Kôshirô to Tsukuhae (Onchi Kôshirô and Moonglow: 恩地孝四郎と月映). Tokyo: National Museum of Modern Art, 1976, nos. 27-42.

- Jenkins, Donald: Images of a Changing World: Japanese Prints of the Twentieth Century. Portland Art Museum, 1983, pp. 83-84..

- Merritt, Helen and Yamada, Nanako: Guide to Modern Japanese Woodblock Prints, 1900-1975. University of Hawaii Press, 1992, pp. 141, 179-181, 183, 185, 251, 276, 278-279, and 282.

- Merritt, Helen: Modern Japanese Woodblock Prints: The Early Years. Honolulu: University of Hawai'i Press, 1990. pp. 137, 178-185.

- Nihon no hanga: 1911-1920 (Japanese prints 1911-1920). [Kizemareta "kojin" ni kyoen: A carved "private" banquet]. Chiba City Museum of Art. 1999, pp. 70-71; also p. 123, nos. 265-1 to 265-4 (Onchi).

- Inoue, Yoshiko, Fujimoto, Manami, Teraguchi, Junji: Tsukuhae (Moonglow — Tanaka Kyôkichi, Fujimori Shizuo, Onchi Kôshirô: 月映 田中恭吉 藤森静雄 恩地孝四郎). Museum of Modern Art, Wakayama (和歌山県立近代美術館). NHK Puranetto Kinki (NHK Planet Kinki: プラネット近畿), 2014.

- Matsumoto Tôru, Kumada Tsukasa, Inoue Yoshiko, Onchi Kôshirô. National Museum of Modern Art, Tokyo and the Museum of Modern Art, Wakayama, exhibition catalogue, Tokyo 2016, pp. 102-103, 116-117, nos. P93-P96, P111, P135, P137-P138.

- de Sabato Swinton, Elizabeth: Terrific Tokyo: A Panorama in Prints from the 1860s to the 1930s. Worchester Art Museum, 1999.

- Smith, Lawrence: Modern Japanese Prints 1912-1989. London: British Museum Press, 1994, pp. 22 and 43, cat. 10, and plate 11.

Viewing Japanese Prints |