KAWANISHI Hide (川西英)

|

Kawanishi Hide (川西英 1894-1965), whose given name was Hideo, was born and worked in Kobe, an international port city that inspired nearly all of his subject matter. He was employed as a postmaster, but his ancestors were merchants, particularly traders in several alcoholic spirits — sake (酒 or nihonshu 日本酒), miring (味醂), and shôchû (焼酎) — which they transported to Tokyo in their fleet of ships. Kawanishi's family opposed his becoming involved in painting and printmaking. Despite working all his life as an artist, he apparently never made a living from it.

Kawanishi Hide (川西英 1894-1965), whose given name was Hideo, was born and worked in Kobe, an international port city that inspired nearly all of his subject matter. He was employed as a postmaster, but his ancestors were merchants, particularly traders in several alcoholic spirits — sake (酒 or nihonshu 日本酒), miring (味醂), and shôchû (焼酎) — which they transported to Tokyo in their fleet of ships. Kawanishi's family opposed his becoming involved in painting and printmaking. Despite working all his life as an artist, he apparently never made a living from it.

A self-taught artist, Kawanishi started painting in oils, but turned to woodblock printmaking after seeing a print by Yamamoto Kanae (A small bay in Brittany) displayed in a shop window in Osaka. He was not interested in ukiyo-e, although Nagasaki-e naturally fascinated him, with its exotic ships and foreign traders. Gradually abandoning oils, Kawanishi fell under the influence of the Art Deco poster style of the 1920s and first exhibited prints in 1923 with the Nihon Sôsaku Hanga Kyôkai (Japan Creative Print Association 日本創作版画協会 founded 1918). Other influences were Onchi Kôshirô, Yamamoto Kanae, and European artists such as Lautrec, Gaugin, Van Gogh, Leger, and Matisse. Kawanishi was awarded the Hyôgo Prefecture Culture Prize (1949) and the Kobe Shinbun Peace Prize (1962). His son Kawanishi Yûzaburô (1923-2014) worked in his father's style, but with more international subjects.

Kawanishi used poster colors and sumi (Japanese carbon black, i.e., soot, water, and glue), cutting his blocks with a curved chisel to obtain soft edges. He said, "There's a feeling of incompleteness, but there is a certain beauty in incompleteness...." He used two types of fine-grained wood for his blocks: katsura (Judas tree: 桂) and ho (magnolia: 朴), and printed on hodomura (程村) paper. He produced a large number of single-sheet designs (more than 1,200), some included in printed albums and books, and sets or series. The latter included Shôwa bijin fûzoku jûnitai (Twelve customs of beauties from the Shôwa era), 1929, and Kobe jûnigagetsu fûkei (Scenes of Kobe during the twelve months), 1931. Another series, Hanga Kobe hyakkei (Prints of one hundred views of Kobe), 1935, is documented only by its preparatory paintings (Kobe City Museum has 95, a private collection has four, and the location of the last design is unknown.) So-called "prints" from Hanga Kobe hyakkei are actually photo-offset lithographs.

Kawanishi recorded (seemingly) all of his designs in notebooks. These works total 1,227, although some of the catalogued designs lack dates or have the same titles as others, making it difficult to match up all his known prints with titles. Still, the number represents a good estimate of his prolific output that was certainly unusual for a sôsaku hanga artist. Further complicating matters is the lack of edition numbers, leaving researchers to guess at how many impressions of a given design might have been printed, whether self-printed or produced by artisans. Kawanishi's designs were made without keyblock lines, as he printed only with color blocks. His self-printed works were made in an expressive style with softer edges to the color areas and shapes, whereas impressions made by artisans working for publishers, or later those done by his son Yûsaburô, have sharper or more well-defined edges, giving the designs a more controlled appearance.

Kawanishi recorded (seemingly) all of his designs in notebooks. These works total 1,227, although some of the catalogued designs lack dates or have the same titles as others, making it difficult to match up all his known prints with titles. Still, the number represents a good estimate of his prolific output that was certainly unusual for a sôsaku hanga artist. Further complicating matters is the lack of edition numbers, leaving researchers to guess at how many impressions of a given design might have been printed, whether self-printed or produced by artisans. Kawanishi's designs were made without keyblock lines, as he printed only with color blocks. His self-printed works were made in an expressive style with softer edges to the color areas and shapes, whereas impressions made by artisans working for publishers, or later those done by his son Yûsaburô, have sharper or more well-defined edges, giving the designs a more controlled appearance.

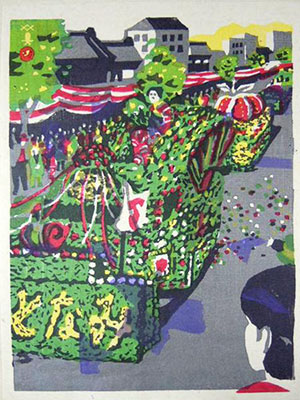

Perhaps no subject is more closely identified with Kawanishi Hide than scenes in and around Kobe Harbor, including views of the city's annual harbor festival. When he contributed a design to the album Nihon minzoku zufu (Folk customs of Japan, illustrated: 日本民族図譜, a portfolio of 12 woodblock prints by ten artists published by Uemura Masuo of Fugaku Shuppansha in 1946), Kawanishi provided a commentary for an accompanying pamphlet. Titled Kobe minato no matsuri (Kobe port festival: 神戸港の祭), he wrote, "The interesting characteristic of this festival was that the parade on land was organized by the foreigners in the Kobe area and by the Japanese as well. The international parade presented Miss Kobe in front of the decorative floats made by people from different nations. At the beginning, Miss Kobe dressed as a Western princess to add an exotic feeling to the parade. But later she wore a beautiful Japanese kimono. After World War II, I was sure that the International Port Festival would have been continued. Unfortunately, the word "international" was taken away and "port" became a part of the festival name. I am hoping that the Kobe Port Festival can be revived before this picture becomes only a memory of the past." Kawanishi's design is shown above left. An exuberantly festooned float (followed by others trailing behind) makes it way down a street during the port festival. Flower petals have fallen from the decorations and now are scattered in the street. A young woman, tucked in the lower right corner of the pictorial space, watches the festivities while crowds of onlookers can be seen on the opposite side of the street. Her left shoulder is shown partly below the lower edge of the main image, creating the illusion that she is looking from outside the picture frame. The beauty on the float may indeed be the aforementioned "Miss Kobe" adorned in colorful Japanese kimono.

After the Second World War his designs took a slight turn toward abstraction, dispensing with waves or identifiable waterfront or hillside landmarks. Buildings and ships tended to blend even more than before, and no well-known structures appear in the views. In the example shown below, his beloved pilot boat remains in the forefront. Note the "straight-out-of-the-paint-tube" intensity of the poster colors, with no gradations, and the simplification of forms — all hallmarks of the artist's printmaking style. The vast majority of Kawanishi's scenes of Kobe Harbor are in small to medium-format size, but this example is a large double ôban.

|

| Kawanishi Hide: Untitled view of Kobe harbor Self-printed and self-published, c. 1953 (large-ôban size, 39.5 x 55.3 cm) |

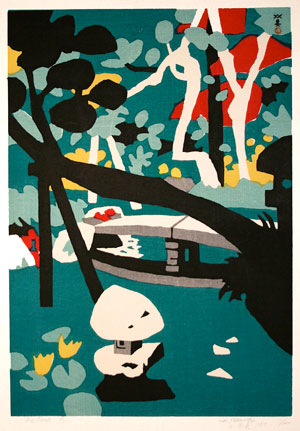

There are some fine views of gardens and ponds in Kawanishi's oeuvre. The design illustrated at the top of this page is titled "The Pond" in English and Ike (池) in Japanese from an edition of 200 in 1957, with an image size of 483 x 333 mm on paper measuring 591 x 446 mm. The simple shapes and bright palette were typical of Kawanishi's oeuvre. All of Kawanishi's colors were printed without contour lines; thus, black (sumi pigment) was not used for a key block as in traditional prints (ukiyo-e); rather, it served as another option for a color shape without outline. Although Kawanishi claimed Matisse was only an indirect influence (he said Matisse furnished "food" for art), the "Pond" reminds one of the French master's late-career cut-outs. There is even a hint of "dancing" forms in Kawanishi's placement of leaves and flowers.

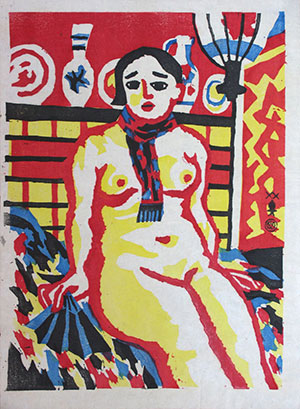

Among his early figure prints is a seated nude from 1933 (see image below left). Brilliant poster colors in a primary palette infuse this portrait with an intensity characteristic of Kawanishi's most boldly expressive works. This design is known in very few impressions. It is not in the artist's catalogue (compiled by the artist's son, Yûzaburô), although it is included as no. 45 in the Kobe City 120th-year anniversary retrospective (see ref. below). A few years later, Kawanishi painted a portrait in watercolors of a young woman dressed in brightly colored kimono with starfish emblems (see below right). Behind her is a picture of a circus horse and a partly visible hanging puppet. The finished prints were published by Katô Hanga Kenkyûsho around 1937 to 1940.

|

|

| Kawanishi: Nude wearing scarf, 1933 (woodcut) | Kawanishi: Young woman, c. 1937-40 (watercolor) |

Kawanishi loved all things foreign. In 1934, for an issue of the coterie art magazine Han geijutsu (Print art: 版芸術) devoted to his works (Kawanishi Hide hangashû, Collected prints of Kawanishi Hide, 川西英版画集), he was quoted as saying, "My interest in exoticism and the foreign influence apparent in my work is due to my growing up in the open port of Kobe. .... I still have vivid memories from my childhood. I could see foreigners and observe their customs in the neighborhoods of Sannomiya and Yamate. I not only have nostalgic memories of foreign customs but also Japanese objects made especially for foreigners."

|

| Kawanishi Hide: A scene from Carmen (Karumeso: カルメソ) from the book with 8 large sheets folded in half Published 1934 by Hanga Sô, Ginza, Tokyo (operated by Hirai Hiroshi) |

It is not clear exactly when Kawanishi might have heard Bizet's opera Carmen, but he was surely thrilled by it. He once recalled, "After Western circuses, Western Theater also frequently came to Kobe. This was an Italian opera troupe. You could see an authentic opera performance that changed every night. However, tickets were expensive and since I am quite poor, it was heart-breaking." Could Kawanishi have also seen the 1929 Japanese film titled Carmen directed by Takeuchi Shunichi? Regardless, in 1933, he designed a single-sheet ôban-size print for each of the four acts, plus an ôban sheet for the eight principal roles with English texts identifying the role names and vocal registers of the singers. Then, in late 1934, he designed different prints with the same scenes for each act, as well as another grouping of small figures in the eight roles. These images were published in Kawanishi's book Carmen (Karumeso: カルメソ). The book was published by Hirai Hiroshi of the firm Hanga Sô, Ginza from blocks carved and proofed in Kawanishi's atelier in Kobe. Shown below is the scene for Act I in which Carmen sings the provocative Habanera ("L'amour est un oiseau rebelle") outside a tobacco factory (the sign "Fabrica de Tabacos" is at the right in Kawanishi's print). While men plead with her to choose a lover, she throws a flower to the soldier Don José.

Kawanishi was fascinated by foreign circuses, although not so with the traditional Japanese circus. As early as 1918, he visited a hippodrome virus and afterward made oil paintings of acrobats, horses, elephants, and other related subjects. He loved the gathering of so many foreign visitors and the strange animals. He first saw a lion at just such a circus, which he later referred to as the "Chiarini Circus," a term once used by the Japanese for any foreign circus, but taken from a much earlier circus run by Giuseppe Chiarini (1823-97), which toured Japan in 1886 and 1889. Kawanishi once said (see D'Orlando ref. below), "When you entered the tent, the smell of the animals, the smell of the circus, would merge into one. My heart captured everything moving before my eyes: the red robe of the animal trainer, with the golden decorations glittering in the light."

|

| Kawanishi Hide: Kyokuba shaseichô (Folding book of circus drawings: 曲馬冩生帖) Published 5/1934 by Hanga Sô, Ginza, Tokyo (operated by Hirai Hiroshi) |

Note: There is some confusion about how a few of Kawanishi's books were produced, but the following seems to be the actual story regarding three publications in particular. Kanai Noriko, curator, Kobe City Museum (Kôbe-shiritsu Hakubutsukan: 神戸市立博物館), who is the world’s authority on the works of Kawanishi Hide, has found that in 1934, Kawanishi teamed up with the Tokyo publisher Hanga Sô to produce three books: two on the circus theme and one on the opera "Carmen." Operated by Hirai Hiroshi, the small publishing firm Hanga Sô was in business from 1/1933 to 9/1936, specializing in limited-edition books from blocks carved by sôsaku-hanga artists. The blocks for Kyokuba shaseichô were carved and proofed in Kawanishi's atelier in Kobe, but then sent to Tokyo and printed on paper derived from the cores of industrial paper cylinders by means of a novel type of machine press (using Kawanishi's blocks). The press was housed in a trade school now known as the Tokyo Institute of Technology, and was operated by their technician. Thus, contrary to what has been written in other sources, the images in these three books, while self-carved, were not self-printed by the artist. The current volume was the second of the circus books. It used more colors and was thus more costly to produce, which required pricing that impeded sales when first released. Today, of course, Kawanishi's circus-themed books and images are quite sought after by collectors.

Kawanishi's renderings of equestrian riders, clowns, acrobats, trapeze artists, lion tamers, seal trainers, and elephant trainers capture the spectacle of the circus in a colorful and playful manner. Kawanishi's fascination with the circus world and his woodcuts detailing the various entertainments, although built upon a different aesthetic, remind us of the American artist Alexander Calder's (1898-1976) line drawings and lithographs on the same themes. Both artists expressed a childlike joy and excitement about the marvels to be witnessed in a circus. © 2019-2020 by John Fiorillo

BIBLIOGRAPHY

- Azechi, Umetarô: Japanese Woodblock Prints: Their Techniques and Appreciation, color plate 5.

- Catalogue of Collections [Modern Prints]: The National Museum of Modern Art, Tokyo (Tokyo kokuritsu kindai bijutsukan shozô-hin mokuroku, 東京国立近代美術館所蔵品目録). 1993, pp. 114-116, nos. 1043-1062.

- D'Orlando, A., de Vries, M, Uhlenbeck, C. and Wessels, E.: Nostalgia and Modernity: The Styles of Komura Settai and Kawanishi Hide. Amsterdam: Nihon no Hanga, spring 2012 (exhibition cat.), pp. 16-18.

- Kawanishi Hide, Gashû "Kôbe hyakkei" Kawanishi Hide ga aishita fûkei (Collected pictures, "100 Scenes of Kobe," favorite scenes of Kawanishi Hide: 画集『神戸百景』川西英が愛した風景), 2008.

- Kobe City Koiso Memorial Museum of Art: (Kawanishi Hide, the retrospective. 120th anniversary of his birth (Kobe shiritsu Koiso kinen bijutsukan (神戸市立小磯記念美術館), Kawanishi hide kaiko ten --- Seitan ichihyakunijû nen (川西回顧展 生誕120年). Kobe: 2014.

- Merritt, Helen and Yamada, Nanako: Guide to Modern Japanese Woodblock Prints, 1900-1975. University of Hawaii Press, 1992, p. 61.

- Lawrence Smith: Modern Japanese Prints 1912-1989. London: British Museum Press, 1994, p. 27 and cat. 20-21.

- Statler, Oliver: Modern Japanese Prints: An Art Reborn. Rutland, VT: Tuttle Co., 1956, pp. 114-118, plate no. 65, 70, 71.

- Uhlenbeck, C., Newland, A.R., de Vries, M.: Waves of renewal: modern Japanese prints, 1900 to 1960, Selections from the Nihon no hanga collections, Amsterdam. Hotei Publishing, 2016, pp. 240-246.

Viewing Japanese Prints |