TORII Kotondo (鳥居言人)

|

Torii Kotondo (鳥居言人 1900-1976) was born Saitô Akira (斎藤信) in the Nihonbashi district of Tokyo. He was adopted at age fifteen by Torii Kiyotada IV (鳥居清忠 1875-1941), the seventh head of the Torii school of ukiyo-e artists, who gave him the art name "Kotondo" (also pronounced "Genjin," 言人). It was with Kiyotada IV that Kotondo trained in the Torii school's specialty — yakusha-e (pictures of kabuki actors: 役者絵). Kotondo also studied with the painter of yamato-e ("Japanese pictures": 大和絵) Kobori Tomone (小堀鞆音 1864-1931) around 1917 and with Kaburagi Kiyokata (鏑木清方 1878-1973) from 1918, whose specialty was bijinga (pictures of beautiful women: 美人画). Starting in 1922, Kotondo began signing his painted bijinga as "Masahiko," which he continued to do for most of his paintings of beautiful women.

Torii Kotondo (鳥居言人 1900-1976) was born Saitô Akira (斎藤信) in the Nihonbashi district of Tokyo. He was adopted at age fifteen by Torii Kiyotada IV (鳥居清忠 1875-1941), the seventh head of the Torii school of ukiyo-e artists, who gave him the art name "Kotondo" (also pronounced "Genjin," 言人). It was with Kiyotada IV that Kotondo trained in the Torii school's specialty — yakusha-e (pictures of kabuki actors: 役者絵). Kotondo also studied with the painter of yamato-e ("Japanese pictures": 大和絵) Kobori Tomone (小堀鞆音 1864-1931) around 1917 and with Kaburagi Kiyokata (鏑木清方 1878-1973) from 1918, whose specialty was bijinga (pictures of beautiful women: 美人画). Starting in 1922, Kotondo began signing his painted bijinga as "Masahiko," which he continued to do for most of his paintings of beautiful women.

At about the age of fourteen or fifteen, Kotondo designed his first yakusha-e woodcut signed "Kotondo" for the short-lived magazine Shin Nigao ("New Portraits": 新似顔). At that time he also contributed illustrations to the more successful Engei gahô (Magazine of the theater: 演藝畫報 1907-1943). His first exhibited work might have been a painting titled Jibo (Affectionate mother: 慈母) at the tenth annual Kyôdokai (Homeland Society: 家園學會) exhibition in 1925.

Throughout his career, Kotondo designed stage scenery and theater programs and billboards for the kabuki theater. This was especially the case the Shinbashi Enbujô or Shinbashi Playhouse, 新橋演舞場 in Tokyo starting around 1926, beginning around a year after the theater opened. These activities proved to be a primary source of income For Kotondo. When Kiyotada IV died in 1941, Kotondo became the eighth head of the school and took the name Kiyotada V, continuing the great lineage dating back to 1687 (Torii Kiyonobu I). Meanwhile, he painted bijinga under the names of "Masahiko" and "Kotondo"; later on, one of his paintings was exhibited in the Nihon bijutsu tenrankai (Japan Fine Arts Exhibition: 日本美術展覧会) exhibition of 1952. He also worked as an art director for theaters in Tokyo and as an art consultant for television; both roles included ensuring that period productions were historically accurate. Later, from 1966 until 1972, he taught art classes at Nihon Daigaku (Nihon University: 日本大学).

There is in Kotondo's bijinga a certain measure of nostalgia. He did not depict beauties adorned in the latest fashions, and certainly not as women who somewhat defiantly wore Western-influenced clothes and accessories. Kotondo's subject was a modern exemplar who still embraced traditional values. We are given intimate glimpses into their ways of dress, makeup, hairstyles, and demeanor — all perfectly fitting for Japanese and Western connoisseurs of prints and paintings who favored a look back at an older Japan that seemed to be disappearing by the 1930s.

There is in Kotondo's bijinga a certain measure of nostalgia. He did not depict beauties adorned in the latest fashions, and certainly not as women who somewhat defiantly wore Western-influenced clothes and accessories. Kotondo's subject was a modern exemplar who still embraced traditional values. We are given intimate glimpses into their ways of dress, makeup, hairstyles, and demeanor — all perfectly fitting for Japanese and Western connoisseurs of prints and paintings who favored a look back at an older Japan that seemed to be disappearing by the 1930s.

Nearly all of Kotondo's woodblock prints were bijinga, totaling 22 known designs issued from 1929 to 1936. All were in large-ôban format (images ~ 410 x 260 mm; paper ~ 465 x 295 mm) as issued by the joint publishers Sakai/Kawaguchi (酒井 and 川口) or by Ikeda Tomizô (Ikeda Shoten: 池田書店). The one exception was a design titled Satsukibare (Fine weather in early summer: 五月晴), a small (181 x 121 mm) woodcut used as a kuchi-e (口絵) or inserted frontispiece for the May 1936 issue of Ukiyo-e kai (Ukiyo-e World: 浮世絵界) published by Ukiyo-e Dôkôkai (see image at left). Many published sources omit this design and thus conclude there were but 21 bijinga by Kotondo. (See Newland 2000 ref. below for an undated illustration; also see Marks 2015 for date information.) In 1941 Kotondo turned briefly to the theater in his printmaking, although he produced only two known works. One was a large shini-e (memorial or "death" print: 死絵) for the nagauta ("long song": 長唄) singer Yoshimura Ijûrô VI (1859-1935). The other design shows the kabuki hero Watônai (和藤内) wrestling a tiger in the play Kokusenya Kassen (Battles of Coxinga: 國性爺合戦).

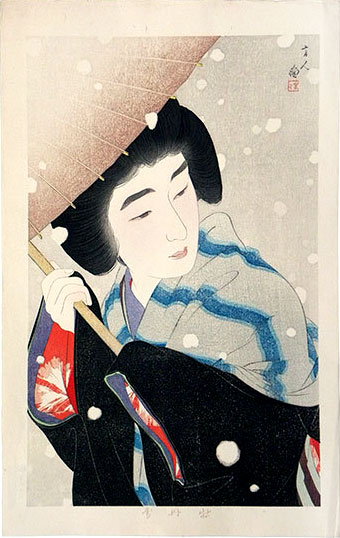

The image above right, titled Botan yuki (Peony snow: 牡丹雪) from circa 1931-34, was published by Ikeda in an edition of 100 in large-ôban format (463 x 293 mm paper). The blocks were carved by C. Itô and printed by Komatsu Wasakichi. The young woman, wrapped up in warm winter robes, grips the umbrella handle and leans into the wind as snow falls. The term botan yuki used for the print title is found in Japanese literature and poetry as a reference to snowflakes as large as the blossoms of a peony bush.

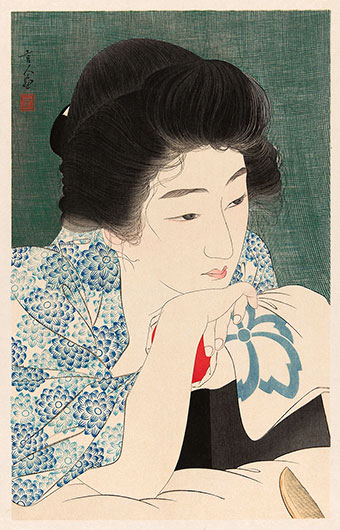

An earlier work by Kotondo from circa 1930 was titled Asanegami (lit., "Hair of a late riser," or perhaps colloquially "sleepyhead," but more commonly called "Morning hair": 朝寝髪). Published by Ikeda in an edition of 100, the blocks were carved by Maeda Kentarô and printed by Maejima in large-ôban format (462 x 298 mm paper). A young beauty seems lost in thought as she lies in bed, propping her chin up on her takamakura ("high pillow": 高枕), a cradle for the base of the neck with a stuffed pad placed on a lacquered-wood support. It was meant to protect elegant coiffures from being ruined during sleep. The woman's hair is nevertheless somewhat disheveled and a comb is partially visible at the lower right.

An earlier work by Kotondo from circa 1930 was titled Asanegami (lit., "Hair of a late riser," or perhaps colloquially "sleepyhead," but more commonly called "Morning hair": 朝寝髪). Published by Ikeda in an edition of 100, the blocks were carved by Maeda Kentarô and printed by Maejima in large-ôban format (462 x 298 mm paper). A young beauty seems lost in thought as she lies in bed, propping her chin up on her takamakura ("high pillow": 高枕), a cradle for the base of the neck with a stuffed pad placed on a lacquered-wood support. It was meant to protect elegant coiffures from being ruined during sleep. The woman's hair is nevertheless somewhat disheveled and a comb is partially visible at the lower right.

In the increasingly conservative social climate leading up to the Second World War, the role of women came under intense scrutiny. Witness, for example, the clash between the modan garu (modern girls, モダンガル or moga, モガ) and the arbiters of propriety in which jazz-age fashions and pleasure-seeking behaviors were criticized and repeatedly suppressed. According to one source (see Nihon Ukiyo-e Kyôkai ref. below), authorities considered Kotondo's print Asanegami to be provocative and so banned it after seventy of its 100 impressions had sold, whereupon they also destroyed the remaining thirty copies. It isn't clear exactly why the print was found to be offensive, but one suggestion (unconfirmed) is that Kotondo's "sleepyhead" was not an innocent maiden, but a female thinking about the previous night's sexual pleasures. Even so, the term asanegami has an eminent pedigree, dating at least as far back as the Man'yôshû (Collection of ten thousand leaves: 万葉集), the first important imperial anthology of Japanese poetry containing 4,516 poems compiled at the end of the eighth century. The author of the poem and likely the last compiler of the anthology, Ôtomo no Yakamochi (伴家持 c. 716-785), imagines his wife sighing after him since their separation, awaiting his return by spending her nights in a half-empty bed and refraining from combing her asanegami.

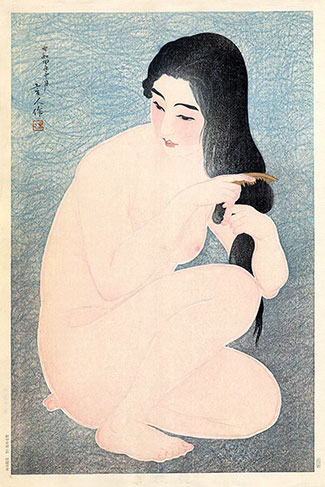

Kotondo twice used the title Kamisuki ("Combing hair: 髪梳き), the first being a nude from 1929 published by Sakai-Kawaguchi on large-ôban paper (411 x 261 mm). The carver was hori (彫) Itô and the printer suri (摺) Komatsu [given name Wasakichi]. Here, the woman is shown having just emerged from a bath, the warm, moist air rendered through printing techniques called gomazuri (printing in sesame-seed pattern: ごま摺) for stippling and baren suji (baren-traces printing: 馬楝筋摺) for swirling lines in the background. The usual black keyblock outlines have been replaced by pink contours, no doubt to suggest the heat absorbed by the body while bathing. The various curves of the body also reflect "feminine" forms.

Kotondo's second Kamisuki subject was issued by Ikeda in an edition of 100 in 1933 on large-ôban paper (473 x 295 mm). As did the earlier Kamisuki design, this print includes the tilted head and the woman's right arm and hand crossing over the body as her index finger extends along the length of the comb. Gomazuri and baren suji printing were also employed by the printer. However, the usual black keyblock outlines define the forms, modulated in a calligraphic manner.

|

|

| Torii Kotondo: Kamisuki (髪梳き), 1929 Pub: Sakai-Kawaguchi (411 x 261 mm) |

Torii Kotondo: Kamisuki (髪梳き), 1933 Pub: Ikeda (473 x 295 mm |

In 1943, Torii Kiyotada IV's student Ueno Tadamasa (鳥居忠雅 1904-1970) was assigned the task of painting theatrical billboards for the Torii school. After Ueno died In 1970, Kotondo reassumed that responsibility. Meanwhile, his daughter Setsuko (b. 1938), a graduate of the Tokyo University of Arts and Music (since 1949 called Tokyo Geijutsu Daigaku, or Tokyo University of the Arts, 東京藝術大学), had earlier assisted her father on certain projects, for example, painting the color areas of theatrical billboards after he had painted the outlines of the figures and other forms. Working alongside her father, she mastered the essential Torii techniques and mannerisms. When Kotondo died in July 1976, Setsuko took over the leadership of the Torii line, not long after becoming the ninth-generation head in 1982 while taking the name "Kiyomitsu." She thus became the first woman to assume the leadership in the more than 300-year history of the Torii school. She has since continued in the tradition of painting theatrical signboards as well as producing kabuki print designs. © 2020 by John Fiorillo

BIBLIOGRAPHY

- Hickman, Money: "Enduring Alliance: The Torii Line of Ukiyo-e Artists and Their Work for the Kabuki Theatre," in: Trustees of the Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum, Fenway Court. Boston:, 1992, pp. 60-84.

- Hockley, Allan (ed.): The Women of Shin Hanga: The Judith and Joseph Barker Collection of Japanese Prints. Hanover, New Hampshire: Hood Museum of Art, Dartmouth College, 2013, pp. 200-215, nos. 49-55a.

- Marks, Andreas: Seven Masters: 20th Century Japanese Woodblock Prints from the Wells Collection. Minneapolis Institute of Arts, 2015, pp. 185-188.

- Merritt, Helen: Modern Japanese Woodblock Prints. The Early Years. University of Hawaii Press, 1990, pp. 81-84.

- Merritt, Helen, and Yamada, Nanako: Guide to Modern Japanese Woodblock Prints, 1900-1975. Honolulu: University of Hawai'i Press, 1992, p. 155.

- Nihon Ukiyo-e Kyôkai (ed.) [Ukiyo-e Society of Japan]: Torii ha sanbyakunin to kyûdaime Kiyomitsu ten. Tokyo: Yomiuri Shinbun, 1990, pl. 102.

- Newland, Amy Reigle and Hamanaka, Shinji: The female image: 20th century prints of Japanese beauties. Leiden: Hotei Publishing, 2000, pp. 125-140, 212, nos. 167-188.

- Stephens, Amy Reigle (Ed.): The New Wave: Twentieth Century Japanese Prints from the Robert O. Muller Collection. London & Leiden: Bamboo Publishing & Hotei Japanese Prints, 1993, pp. 198-203, nos. 262-271.

- Till, Barry, Wargentyne, Michiko, and Patt, Judith. "From Geisha to Diva. The Kimono of Ichimaru," in: Arts of Asia, May–June 2003, vol. 33, no. 3.

- Toledo Museum of Art: A Special Exhibition of Modern Japanese Prints. Toledo, Ohio: 1936, no. 127-143.

Viewing Japanese Prints |